The islands of Britain and Ireland weren’t always an archipelago. The lands we now stand on were once connected to mainland Europe. Around 7000 BC, both Britain and Ireland were part of a landmass known as Doggerland—a vast, low-plain region that bridged what is now the North Sea with the continent. This area was inhabited by various animals, plants, and our ancestors: Homo sapiens.

As sea levels rose after the Ice Age, Doggerland was flooded, severing the British and Irish Isles from the mainland. Yet, migration to these lands had already been occurring for hundreds of thousands of years before they became isolated islands.

Our History: A Reality Check

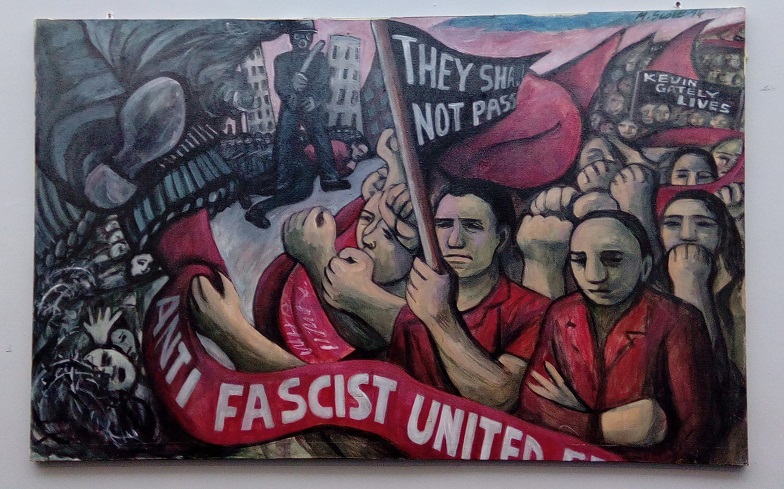

The right-wing belief that the British and Irish Isles have always belonged to “one homogenous group” of people is pure fantasy—one that has been propagated by white supremacist and fascist ideologies for decades. People have been arriving here, settling, and shaping this landscape for millennia.

When people tell you immigration is a problem, ask yourself: who benefits from that narrative? Given our deep history of migration, the right-wing rhetoric against it is absurd. Migrants have been central to the story of these isles, long before borders, nation-states, or even Homo sapiens existed.

The True Natives: Before Homo sapiens

It’s wild to think that the earliest known inhabitants of what is now the Irish and British Isles weren’t even modern humans. Homo heidelbergensis, an extinct species of early humans, roamed these lands around 500,000 years ago. Fossil evidence of these early hunter-gatherers has been found at Boxgrove in Sussex, a site I’d love to visit myself one day.

As the climate shifted between glacial and interglacial periods, multiple species migrated in and out of the region. After Homo heidelbergensis, another cousin species—Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis)—had arrived. They lived here during warmer periods between Ice Ages, hunting, making tools, and likely forming social groups not too dissimilar from ours.

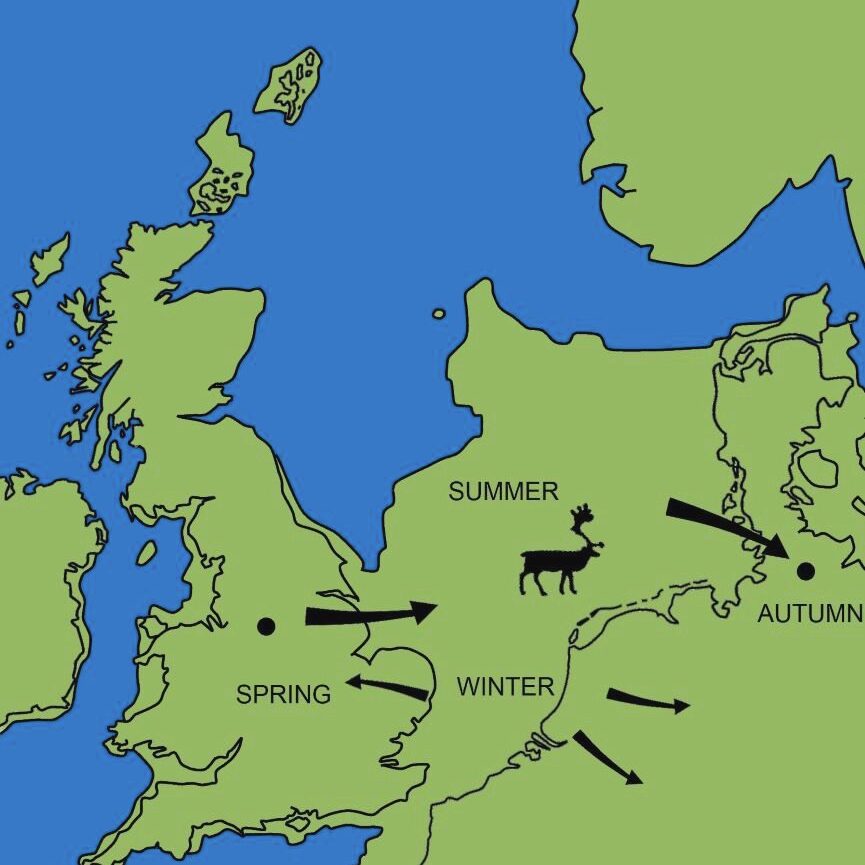

Neanderthals traversed between northern Europe and the lands we now call Ireland and Britain, following herds of animals and relying on fishing and foraging to support themselves. These early migrations weren’t just humans moving around; entire ecosystems were shaping the land and those who lived on it too.

Homo sapiens and the Movement of Peoples

Around 40,000 years ago, Homo sapiens—modern humans—began to arrive, coexisting for a time with our Neanderthal cousins. We know this because genetic studies show that the majority of people outside of Africa carry traces of Neanderthal DNA (around 1% to 2%).

For thousands of years, different species of humans shared this space, mingling and surviving alongside one another long before these lands were even islands. Neanderthals eventually went extinct, leaving Homo sapiens as the dominant human species. This period of coexistence and occasional interbreeding shows how migration and interaction between different human species have always been part of these lands’ history.

Continent to Archipelago: The Flooding of Doggerland

At the end of the last Ice Age, Doggerland was a rich, fertile land bridge between Britain and continental Europe. It was a migration route for animals and humans alike until rising sea levels submerged it about 8,000 years ago. Despite the flooding, people continued to migrate to the British and Irish Isles, even as they became isolated islands over time.

Neolithic Revolution and Beyond

The islands’ history of migration didn’t stop there. Around 4000 BC, Neolithic farmers from places as far as Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) arrived. They brought with them revolutionary ideas about farming and community living. Their descendants built Stonehenge, around 3000 BC, a monument that still stands as a testament to the communal efforts of these early migrants.

After this, the Isles saw multiple waves of migration. The Celts arrived, followed by Roman conquest and settlement. The Anglo-Saxons migrated from continental Europe, and the Norse Vikings raided and eventually colonised parts of the islands. Finally, the Normans invaded in 1066, dramatically reshaping the culture, language, and politics of the region.

This constant flow of people, cultures, and ideas has always been part of the DNA of these lands.

Fuck The Fascist Myth of “Purity”

The idea that these islands have ever been homogenous is a joke. But here we are today, with governments and right-wing fascists trying to rewrite history, telling you that the people who come here are the enemy, and that the land belongs to some mythical indigenous group.

That lie? It’s dangerous. It’s the same rhetoric used to divide us and pit people against one another. They wrap it up in nationalist flags, stoked by governments desperate to fuel culture wars. But why? The history of the British and Irish Isles clearly shows us the opposite of that ideology—there’s no such thing as a “native” population here. We’ve always been shaped by migration.

White supremacists and fascists cling to the idea that these islands once belonged to a homogeneous group, but the archaeological, genetic, and historical evidence tells a very different story. This idea is propagated by those who seek to exclude others via violence and hate, to claim a mythical “right” to the land that has never existed in reality.

Final Thoughts

The narrative of “purity” has been weaponized by those who wish to maintain control. It’s the same governments that want you to look at your neighbour as the enemy, not the systems that actually oppress you. It’s the same groups that want to keep you ignorant about the long, complex, and beautiful history of human migration that has always defined these islands.

It’s the kind of narrative designed to divide us, to keep us fighting each other instead of coming together. But we’re not here for their fairy tales. This isn’t a story for fascists. This is for the people who want to learn about where we really come from.

Immigration isn’t an interruption in the story of the British and Irish Isles—it is the story. From prehistoric migrations of different human species to more recent capitalist, war- and climate-induced migrations, this history doesn’t belong to the racists. It doesn’t belong to the fascists. It belongs to all of us.

Sources:

- Stringer, C. (2012). The Origin of Our Species. London: Penguin.

- Pinhasi, R., & Stock, J. T. (2011). Human Bioarchaeology of the Transition to Agriculture. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Gaffney, V., Fitch, S., & Smith, D. (2009). Europe’s Lost World: The Rediscovery of Doggerland. CBA Research Reports.

- Green, R. E., et al. (2010). “A Draft Sequence of the Neanderthal Genome.” Science, 328(5979), 710-722.

- Higham, T., et al. (2014). “The timing and spatiotemporal patterning of Neanderthal disappearance.” Nature, 512(7514), 306-309.

- Brace, S., et al. (2019). “Ancient genomes indicate population replacement in Early Neolithic Britain.” Nature Ecology & Evolution, 3, 765-771.

- Cunliffe, B. (2013). Britain Begins. Oxford University Press.

Leave a Reply